The first ski resort in Europe without ski lifts In northern Italy, Homeland aims to offer an alternative and more sustainable ski experience, for those willing to walk "We all loved the idea of promoting this more sustainable, human-powered form of skiing" Walter Bossi, director of Homeland

“The old smugglers would have loved it,” said Giacomo Casiraghi, as the clouds approached and the snow began to fall in thick, heavy flakes. We were ski mountaineering above the Spluga Pass, on the border between Italy and Switzerland, a border delimited by 3,000 meter peaks now completely hidden from view. On the way up, Giacomo told us how local smugglers, or smugglers, waited for conditions like this to hide from the prying eyes of customs police in the town of Montespluga below. “Every now and then, they would get spotted and have to throw away their loot,” he said. "People say that even today you can find treasures in these mountains, if you know where to look." We had reached the Val Loga bivouac, a small unmanned refuge at 2,750 m, when we decided to turn around. We were well above the tree line and the weather wasn't going to improve anytime soon. Perfect conditions perhaps for bootlegging, less so for bootpacking on the final ridge. I was happy to be able to follow Giacomo, an experienced mountain guide, who knows these mountains better than any smuggler, as we began to descend the almost featureless powder field. If the visibility was less than ideal, the snow was fantastic. As rocks and other landmarks began to emerge from the white, my friend Daniele Micheli and I gained more confidence, opening the throttle with each successive lap and launching larger and larger arcs of spray. When we reached the bottom, we had smiles on our faces and snow stuck to our glasses. Even the day before, when we arrived in Montespluga, it was snowing. From Bergamo, our route took us along the eastern shore of Lake Como (“The economic side, not the George Clooney side,” said Daniele), before following a series of 41 dizzying hairpin bends through the clouds. Sometimes we could barely see the edge of the road. But every few turns, an old carriage house with a steeple emerged from the fog. “In 1600 they built them every three kilometres,” Giacomo told me later. “The road is so steep that people needed fresh horses so often. When there was a blizzard, they would ring the bells so that travelers could follow the sound."

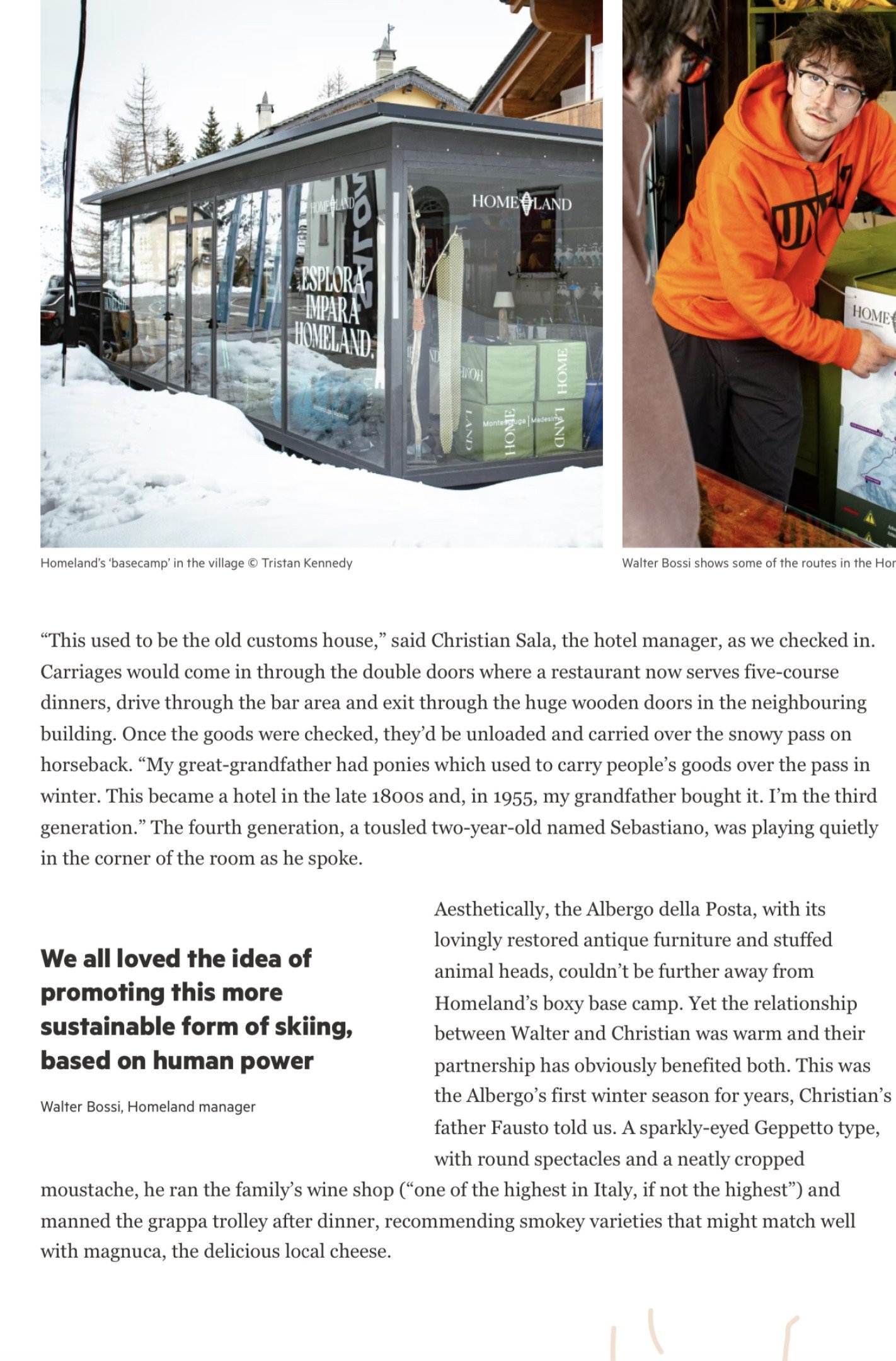

At first glance Montespluga, the last settlement before the border, seemed not to have changed much since those bells stopped ringing. But when we stopped in front of a beautiful 17th century church, we saw something strange. A basic rectangular structure with three sides of glass sat on one side of the old village square, as alien as a spaceship landing on a National Trust lawn. On the front, in bold letters, was an English word: Homeland.

Launched earlier this year, Homeland is billed as Europe's first lift-free ski resort, where ski tourers can climb 11 signposted uphill routes and then descend wherever they like in a vast area encompassing 9,000 acres of terrain off-piste. (They pay nothing for the privilege.) Inside the rectangular cabin, manager Walter Bossi and his colleague Eduardo Perego proudly showed us their brand-new rental gear: big touring skis, splitboards, and backpacks filled with the essentials anti-avalanche kit consisting of ARVA, shovel and probe. A shelf behind them held expedition tents and all-season sleeping bags, for overnight excursions. In the corner was a rack for drying skins and a bench for storing and repairing skis. In the après-ski relaxation area that they had set up in the other half of the structure, Walter and Eduardo made us a coffee, lay down on the blue cushions with the Homeland brand and explained how the project was born. The concept was first conceived by Tommaso Luzzana and Paolo Pichielo, co-founders of an events agency based in Milan. “They are both avid skiers and had time on their hands during the pandemic,” explained Walter, who began working with the couple shortly after they came up with the idea. The eureka moment came, he says, when they read an article about Bluebird Backcountry, a ski-touring-only resort in Colorado.

According to a March 2023 report by Legambiente, the country's main environmental NGO, the Italian ski industry has been severely affected by climate change, with several resorts closed and nearly 400 ski lifts abandoned. Italian resorts are more dependent on artificial snow than other major ski destinations. But, like ski lifts, snow cannons use colossal amounts of energy, ultimately contributing to the crisis they are designed to solve. Ski mountaineering offers an alternative route. “We all liked the idea of promoting this more sustainable, human-powered form of skiing,” Walter said. They knew that Montespluga, just two and a half hours from Milan, offered a huge potential market, excellent terrain and an enviable snowfall record. Ski touring can often be prohibitively expensive but, offering rental kits at reasonable prices (€55 per day only for skis, boots and skins or €65 with the complete avalanche kit), Homeland hopes to make it more accessible. Giacomo Casiraghi's company, Mountain 360 Guides, has been involved to organize regular safety courses and introduction days to ski mountaineering for beginners (both starting from €100 per person, per day). And an old hotel in the village, the Albergo della Posta, will now remain open for the winter to welcome visiting skiers.

“This was the old customs house,” said Christian Sala, the hotel manager, as we checked in. The carriages entered through double doors where a restaurant now serves five-course dinners, passed through the bar area and exited through the huge wooden doors of the neighboring building. Once the goods had been checked, they were unloaded and transported on horseback along the snowy pass. “My great-grandfather had ponies that carried goods over the pass in the winter. This became a hotel in the late 1800s and, in 1955, my grandfather purchased it. I'm the third generation." The fourth generation, a disheveled two-year-old named Sebastiano, played quietly in the corner of the room as he spoke.

Aesthetically, the Albergo della Posta, with its lovingly restored antique furniture and stuffed animal heads, couldn't be further from Homeland's boxy base camp. Yet the relationship between Walter and Christian was warm and their collaboration obviously brought benefits to both of them. This was the hotel's first winter season in years, Fausto, Christian's father, tells us. A twinkling-eyed Geppetto type, with round glasses and a well-trimmed moustache, ran the family wine shop ("one of the tallest in Italy, if not the tallest") and manned the grappa cart after dinner, recommending smoked varieties which could have paired well with magnuca, the delicious local cheese. “In the fifties and sixties, four hotels were open here,” says Fausto. There was also a ski lift and “even when the road wasn't open tourists came here in horse-drawn sleighs.” By the early 1980s, however, numbers had declined. The other hotels closed, one after the other, the ski lift was dismantled and Montespluga became a sort of ghost town in the winter. Until arriving in the homeland. "I believed in it from the beginning," said Kikka Gramigna, who had come from her nearby holiday home to have dinner at the Albergo della Posta. “My parents have been coming here since 1947 and I have been coming here for 70 years.” When the Homeland building first came up, she saw people on Facebook complaining that she was taking up parking space but, even though she no longer skis, she's a fan of hers. “They are bringing life back to the village, there are people coming from Germany, from Austria, from everywhere,” she said. “And their fire, their passion, is fantastic.” The sky was clear on our last day in Montespluga and the early morning sun cast purple shadows beneath the drifts of fresh snow. The skiers in and around Milan had evidently seen the forecast and, although they were not racing, Walter and Eduardo were busy renting several pairs of skis and splitboards, indicating the marked itineraries on the map, giving advice. Kite skiers flew brightly colored sails over the frozen plains of Lake Montespluga and, over the course of a couple of hours, I counted almost 100 tourers shuffling along the main ski slope outside the town. Accompanied by Giacomo's colleague , Nicola Ciapponi, avid telemark skier, we had deviated from the main route to go down a quieter slope on the north side of the valley. The snow would be better here, he said. But as we climbed up and I watched other groups choose their lines, it struck me that the beauty of Homeland was how accessible everything was. You didn't have to know where to look around: there were treasures everywhere.

At first glance Montespluga, the last settlement before the border, seemed not to have changed much since those bells stopped ringing. But when we stopped in front of a beautiful 17th century church, we saw something strange. A basic rectangular structure with three sides of glass sat on one side of the old village square, as alien as a spaceship landing on a National Trust lawn. On the front, in bold letters, was an English word: Homeland.

Launched earlier this year, Homeland is billed as Europe's first lift-free ski resort, where ski tourers can climb 11 signposted uphill routes and then descend wherever they like in a vast area encompassing 9,000 acres of terrain off-piste. (They pay nothing for the privilege.) Inside the rectangular cabin, manager Walter Bossi and his colleague Eduardo Perego proudly showed us their brand-new rental gear: big touring skis, splitboards, and backpacks filled with the essentials anti-avalanche kit consisting of ARVA, shovel and probe. A shelf behind them held expedition tents and all-season sleeping bags, for overnight excursions. In the corner was a rack for drying skins and a bench for storing and repairing skis. In the après-ski relaxation area that they had set up in the other half of the structure, Walter and Eduardo made us a coffee, lay down on the blue cushions with the Homeland brand and explained how the project was born. The concept was first conceived by Tommaso Luzzana and Paolo Pichielo, co-founders of an events agency based in Milan. “They are both avid skiers and had time on their hands during the pandemic,” explained Walter, who began working with the couple shortly after they came up with the idea. The eureka moment came, he says, when they read an article about Bluebird Backcountry, a ski-touring-only resort in Colorado.

According to a March 2023 report by Legambiente, the country's main environmental NGO, the Italian ski industry has been severely affected by climate change, with several resorts closed and nearly 400 ski lifts abandoned. Italian resorts are more dependent on artificial snow than other major ski destinations. But, like ski lifts, snow cannons use colossal amounts of energy, ultimately contributing to the crisis they are designed to solve. Ski mountaineering offers an alternative route. “We all liked the idea of promoting this more sustainable, human-powered form of skiing,” Walter said. They knew that Montespluga, just two and a half hours from Milan, offered a huge potential market, excellent terrain and an enviable snowfall record. Ski touring can often be prohibitively expensive but, offering rental kits at reasonable prices (€55 per day only for skis, boots and skins or €65 with the complete avalanche kit), Homeland hopes to make it more accessible. Giacomo Casiraghi's company, Mountain 360 Guides, has been involved to organize regular safety courses and introduction days to ski mountaineering for beginners (both starting from €100 per person, per day). And an old hotel in the village, the Albergo della Posta, will now remain open for the winter to welcome visiting skiers.

“This was the old customs house,” said Christian Sala, the hotel manager, as we checked in. The carriages entered through double doors where a restaurant now serves five-course dinners, passed through the bar area and exited through the huge wooden doors of the neighboring building. Once the goods had been checked, they were unloaded and transported on horseback along the snowy pass. “My great-grandfather had ponies that carried goods over the pass in the winter. This became a hotel in the late 1800s and, in 1955, my grandfather purchased it. I'm the third generation." The fourth generation, a disheveled two-year-old named Sebastiano, played quietly in the corner of the room as he spoke.

Aesthetically, the Albergo della Posta, with its lovingly restored antique furniture and stuffed animal heads, couldn't be further from Homeland's boxy base camp. Yet the relationship between Walter and Christian was warm and their collaboration obviously brought benefits to both of them. This was the hotel's first winter season in years, Fausto, Christian's father, tells us. A twinkling-eyed Geppetto type, with round glasses and a well-trimmed moustache, ran the family wine shop ("one of the tallest in Italy, if not the tallest") and manned the grappa cart after dinner, recommending smoked varieties which could have paired well with magnuca, the delicious local cheese. “In the fifties and sixties, four hotels were open here,” says Fausto. There was also a ski lift and “even when the road wasn't open tourists came here in horse-drawn sleighs.” By the early 1980s, however, numbers had declined. The other hotels closed, one after the other, the ski lift was dismantled and Montespluga became a sort of ghost town in the winter. Until arriving in the homeland. "I believed in it from the beginning," said Kikka Gramigna, who had come from her nearby holiday home to have dinner at the Albergo della Posta. “My parents have been coming here since 1947 and I have been coming here for 70 years.” When the Homeland building first came up, she saw people on Facebook complaining that she was taking up parking space but, even though she no longer skis, she's a fan of hers. “They are bringing life back to the village, there are people coming from Germany, from Austria, from everywhere,” she said. “And their fire, their passion, is fantastic.” The sky was clear on our last day in Montespluga and the early morning sun cast purple shadows beneath the drifts of fresh snow. The skiers in and around Milan had evidently seen the forecast and, although they were not racing, Walter and Eduardo were busy renting several pairs of skis and splitboards, indicating the marked itineraries on the map, giving advice. Kite skiers flew brightly colored sails over the frozen plains of Lake Montespluga and, over the course of a couple of hours, I counted almost 100 tourers shuffling along the main ski slope outside the town. Accompanied by Giacomo's colleague , Nicola Ciapponi, avid telemark skier, we had deviated from the main route to go down a quieter slope on the north side of the valley. The snow would be better here, he said. But as we climbed up and I watched other groups choose their lines, it struck me that the beauty of Homeland was how accessible everything was. You didn't have to know where to look around: there were treasures everywhere.